This is the story of how Sally Costella came to be a candidate for Senator in the 2010 Australian Federal Election.

In 2009, Sally discovered that her new husband John was a true believer in climate change, and John discovered that Sally was a skeptic. This wasn’t a topic that had ever come up in the year or so since they first met. No big deal, but the challenge to convert the other was immediately and eagerly taken up by both.

John walked down to the local Blockbuster store in suburban Narre Warren South, an hour outside the downtown of Melbourne, Australia, and rented Al Gore’s Academy Award and Nobel Prize–winning film, An Inconvenient Truth. But, being a good physicist, he also rented a few other videos that expressed contrary skeptical views, from what was essentially the “fringe documentary” section. (It is certain that the security cameras would have caught him smirking widely while adding these videos—none of which would have ever even been in the same room as an Academy Award or a Nobel Prize—to the growing pile cradled under his left arm.)

The video-watching session that evening started predictably. John played Gore’s historic film, pointing and beaming smugly at all the key scientific points, self-assured that Sally was being won over. But at the end of the film, Sally was still unconvinced—completely and utterly. Her position had not moved one iota. John was taken aback. What sort of rebellious creature had he married? (But that was the michievous spirit he loved; he would not change it for the world.)

So the fringe skeptical videos came next. John continually laughed and pooh-poohed the various ridiculous anti-science, conspiracy-theory claims made in them. Sally’s facial expression could best be described as “unimpressed cat.”

At some point in the evening, John’s smirk dissolved. The arguments being made about graphs of temperature changes and carbon dioxide levels over archaeological time periods—separating correlation from causation, based on which changes preceded which in time—were not crazy fringe science. They were real science. They were what John would have done if he were doing this research himself. He would have to check the original data sources, of course—they may have been complete misrepresentations or even fabrications—but his rock-solid faith in the “consensus” scientific view of climate change had suffered a significant fracture.

Over the following weeks and months, John’s position on the issue continued to slowly shift. It was clear, from the fundamental atmospheric physics, that the carbon dioxide released by mankind would warm the planet; almost no serious scientist doubted that fact. But the amount that this source has contributed to the rise in historical temperature was the key question. There were two sides to this: the theoretical modeling of the Earth and its atmosphere, and the historical records of both temperature and carbon dioxide.

Both of these seemed to be more uncertain than presented in the “consensus” view.

First, modeling the whole planet is hard. John could see immediately that the models used to date could be described as “simplistic” at best. Worse, the “consensus” view relied on an “amplification” theory, in which the simple atmospheric physics warming would be turbo-boosted by a positive feedback loop due to increased cloud cover. There was no direct scientific evidence for this amplification theory. So there should definitely be warming, but the headline amount was relying on unproven theoretical speculation. As a theoretical physicist, John knew that this was extremely dangerous ground: most theories do not describe the real world, and the few that do generally lead to Nobel Prizes in Physics, not the Peace Prize.

Second, the temperature record seemed to have a tenuous basis. We have not had scientists measuring temperatures around the globe for thousands or tens of thousands of years, and even for most of the past few hundred years our coverage has been spotty. In many cases we rely on “proxies” of temperature—but we can only do that by making use of physical models themselves. It is all quite circular, and not as rock-solid as a “consensus” would imply.

John’s position on the issue was uncertain.

Months later, on November 17, 2009, press reports broke of the leaking of thousands of emails from the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, detailing correspondence between they key scientists responsible for estimating the Earth's historical temperature record. Dubbed “Climategate,” the leak grabbed the attention of the world, just weeks before the Copenhagen Summit on climate change.

John thought that this would finally be a chance to show that the conspiracy theories about climate change were misfounded, and that the emails would show science proceeding as it should, with disagreements and debates and resolutions leading the field haphazardly but relentlessly towards the truth. He downloaded the full repository of emails and started reading them.

After reading just a small random sample, the crack that had appeared in his faith in the science of climate change yawned open into a chasm.

These “scientists” weren’t doing science at all. They were playing politics, bending the science to support their predetermined conclusions. Whatever the truth happens to be about man-made climate change, it could never be based on manipulations like those.

John decided to make the full Climategate repository available on his website, editing (with explicit notation) the scientific jargon into ordinary English so that normal people could grasp its meaning (while linking back to the original email in every case), and color-coding the various authors to make it easier to keep track of the cast of characters. Others started making use of this repository. Some asked whether he could compile all of it into a single document, even before he had finished working through all of the emails.

John’s sudden entry into the field led to him being contacted by people from various climate skeptics’ groups throughout Australia and the world. One was the Lavoisier Group, based in Melbourne itself. John was invited to one of their meetings, at which it was proposed that if he were able to compile his corpus of annotated and color-coded emails into book form, they would arrange to have printed in color a thousand copies to distribute to their members.

And so it came to pass that The Climategate Emails was published in March 2010.

Around the same time, a new political party was created in Australia, The Climate Sceptics Party, in order to stand candidates in the Federal Election due later that year who were skeptical of the science of climate change and opposed to a proposed new federal Carbon Tax. John was contacted by the officers of the Party, ultimately joined the Party, and offered to be the webmaster for the Party, an offer that was accepted. John was now involved for the first time in federal politics.

On July 17, 2010, it was announced that the 2010 Federal Election would be held on August 21, 2010. (In “Westminster” systems like Australia’s, the Prime Minister can call an election at almost any time, within constitutional and legislative restrictions, providing that the request is approved by the Governor-General.)

The Climate Sceptics Party had two Senate candidates ready to run in each of Australia’s six states (the minimum number of candidates required for a viable “ticket”) and candidates for some seats in the House of Representatives.

Shortly after the election was announced, the second Senate candidate for the state of Tasmania pulled out for personal reasons.

The party’s leadership called John, asking if he would consider standing as the second Senate candidate for Tasmania. But there was a problem: by this point in time, John had changed jobs, working now as a cancer researcher at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center in Melbourne, a research hospital owned by the state government. Section 44 of the Australian Constitution bans anyone working for any branch of the government (except for members of parliament themselves) from being a candidate for any federal parliamentary office. The only way that John could run would be to resign his job. Since it was universally acknowledged that John would have zero chance of winning a seat in the Senate as the second member of the Tasmanian ticket, everyone agreed that it would not make sense for him to go into financial ruin.

The next phone call came quickly: would John’s wife Sally be prepared to run? John called Sally quickly, and then called the party leadership back to confirm that she would be willing to have a go. But they lived in Melbourne, in the state of Victoria, not in Tasmania. Could she run for a Senate seat in Tasmania if she didn’t even live there?

It turns out that there is no need for a candidate to actually live in the electorate they are running for. There may be a serious political downside in living somewhere else, but there are no constitutional or legal obstacles.

And so Sally became a Candidate for Senator from Tasmania for the Climate Sceptics Party in the 2010 Australian Federal Election.

John offered to be her campaign manager, webmaster, and correspondence receptionist.

Much of Sally’s positions on various issues, in response to correspondence from a wide variety of political and social issue groups, were posted to this website during the campaign. That material has since been taken down, but is available on request. It may also be available on the websites of some of those groups.

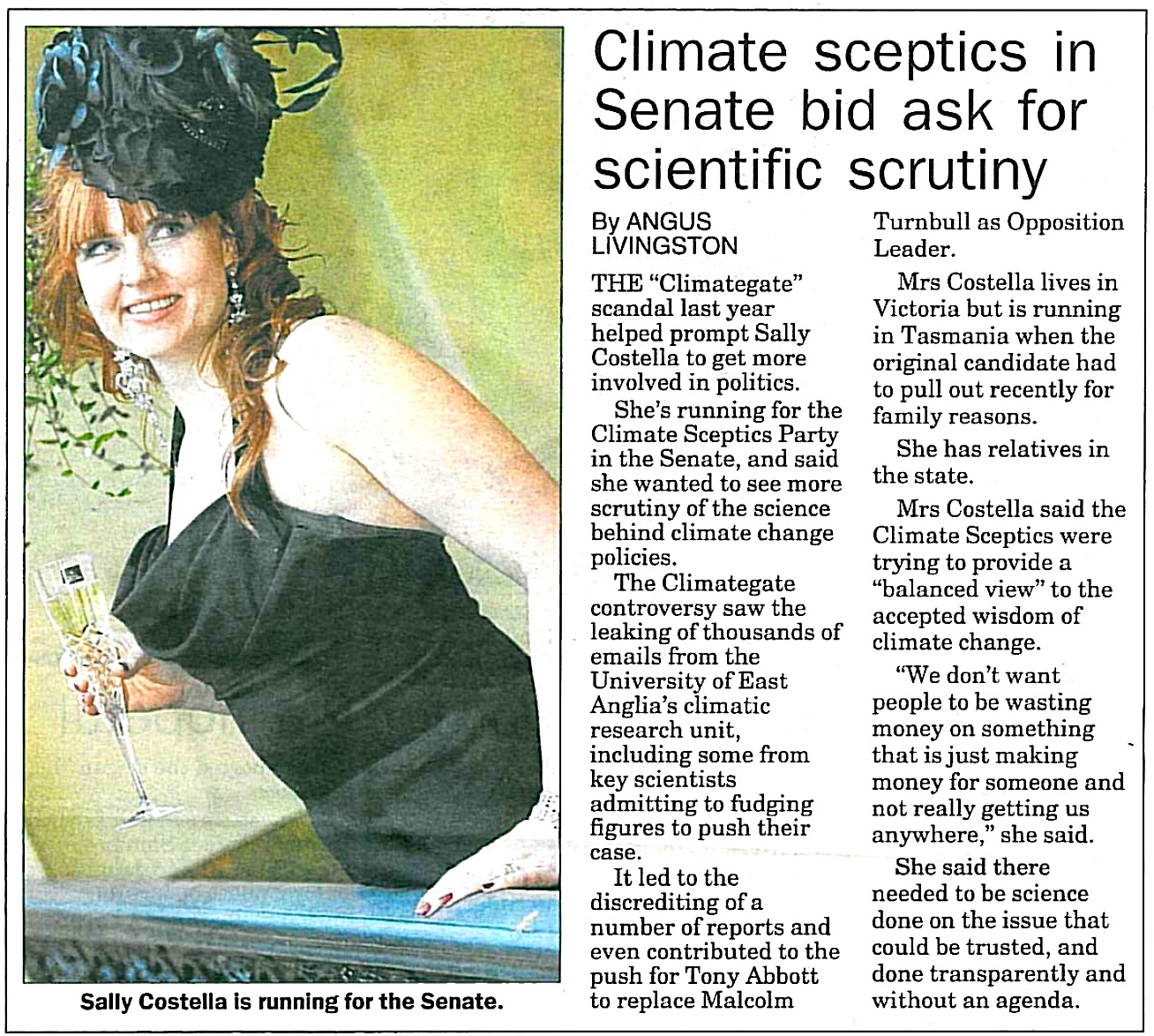

Some weeks into the election campaign, Sally received in the postal mail a newspaper article sent by one of her relatives in Tasmania (at least she does have some connection to the state—John has never even visited it, to this day), which is reproduced below. Storming in to where John was working on his computer, waving the article, John had to explain that when the newspaper reporter called him and asked for a photo of Sally, and with digital photos still not being a big thing in 2010, he had just used one of the photos taken by the wedding photographer on the day of their wedding just over a year earlier and given to them on DVD, thinking it would be a small addition in the corner of the reporter’s story. The actual result has caused much mirth in the years since:

It may not have set Sally up as the most serious candidate in the election, but at least everyone knew that she would be fun!

As expected, Sally did not become a Senator. Sadly, no one from the Climate Sceptics Party won a seat.

Many have asked if Sally might consider running for Parliament again in the future. Unfortunately, since March 10, 2020, the day before the global pandemic was declared, Sally and John have also been a dual citizens of the United States of America, and by Section 44 of the Australian Constitution are thereby banned from running for federal office.

Might Sally run for office one day in the United States? You never know!

© 2022 Sally Costella